Has the world stopped?

In conversation with Caroline Jane Harris

The age-old saying goes, “time flies when you’re having fun” – informing our collective understanding that our emotional state influences the subjective rate at which time passes. Indeed, a recent study, published in the science journal PLoS One (2020), revealed that 80% of the participants consulted said their experience of the passage of time had been distorted since the UK government first imposed lockdown measures in March of this year. It says: “The passage of time during the day was predicted by age, stress, task load and satisfaction with current levels of social interaction. A slowing of the passage of time was associated with increasing age, increasing stress, reduced task load, and reduced satisfaction with current levels of social interaction.”

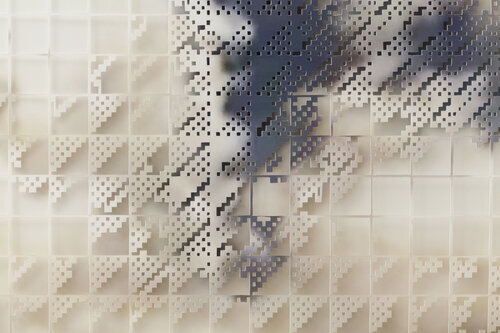

Caroline Jane Harris, Deep, Slow, Still I, 2020, Hand-cut layered digital prints, 90 x 123cm

Since lockdown began, many have commented on the strange phenomenon of days passing slowly with minimal human interaction, and yet we continue to receive information at breakneck speed. Friends on the other side of the world appear on pixelated screens at the touch of a button, yet we become increasingly aware of just how many months have passed since we last saw them. As has been commented on numerous times, when coronavirus hit, it felt like the world stopped. Coincidentally, ‘A Stopped World’ is the title of the latest body of work by British artist, Caroline Jane Harris.

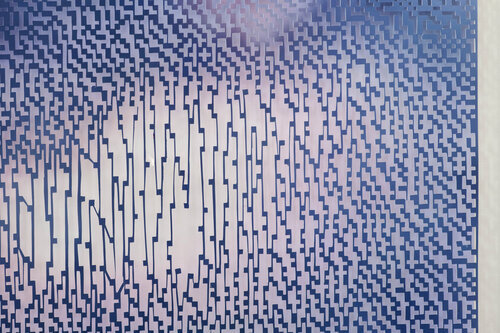

Harris’s work is preoccupied with many of the qualities that have come to define lockdown: our relationship with technology, and the act of looking in a world dominated by screens; our habits of perception and what we know to be true; our experience of time and space.

Ahead of her solo exhibition at Kristin Hjellegjerde Gallery Berlin, Harris spoke to us about her work’s engagement with these topics, and how her practice has evolved over time.

Speaking on the development of her practice, Harris said: “I think it’s important for people to know that my BA was in printmaking, and that informs a lot of the work I continue to make. When you are printmaking, the image also exists as an object because there’s something dimensional about the pushing and pressing into the paper, and the act of layering itself.”

I came to paper cutting through my BA, and then I started doing woodcuts. I noticed that when you are doing woodcuts, the first thing you really see is the style, and the subject is second. I wanted to try and remove that expressionism, and that’s how I came to using photographs. I wanted to keep that human presence, but without too much interpretation, Caroline explains.

Harris’s previous body of work, ‘A Three Dimensional Sky’ (2018-19) used found images she first discovered in a junk shop in Vermont as the basis of her layered pieces. The small glass slides, not much smaller than an iPhone screen, that contain transparent photographs of rolling, cumulus clouds, or giant crashing waves, form the basis of her layered compositions.

Caroline Jane Harris, A Stopped World, 2020, 16 hand-cut layered digital prints, 57 x 88cm each

I was fascinated by how it was both a photograph and a physical object. Because it’s transparent, it functions not unlike a paper cut as it’s got both the solid and the negative. But it’s a piece of history - reduced, and portable. Because of the portability, I liked the idea that people would take them over to their friend’s houses and show them, and it got me thinking that that isn’t so different to how we share images now.

Speaking of her work’s engagement with the natural world, Harris said: “I enjoyed the fact that the subjects I was picking - rolling clouds, mountains, the sea, are all so massive and then you have the opposite extreme, in that they are compressed into this small thing. Again, it’s not so different to how we view the world these days, watching something like a volcanic eruption from the comfort of our own home, on a laptop screen.”

Technology has sped up everybody’s way of being, and of course it’s not all bad, it’s allowing us to sit here and have this conversation now. But we can’t move so fast that we leave everything behind. Part of my motivation, and perhaps it’s a little romantic to say, is that I want us to hang on to the idea that it’s important to re-engage with the act of looking.

Encouraging the viewer to slow down, and absorb her work is important to Harris. In fact, research shows that the average viewer spends just 27 seconds engaging with a piece of art before moving on.

Harris puts an emphasis on the importance of engaging with the work in space, as well as in time. “I really do feel that my work needs to be seen in person. If someone has never seen my work, it’s hard to understand that there’s a space behind every layer of a piece. The work can’t really exist on screens or phones – it has to be experienced. There’s some about it that flies in the face of quick, easy-to-access images we’re all accustomed to. It puts forward the importance of a more slow, engaged viewing,” she says.

“it’s about how we relate to the act of looking, and how our spatial awareness is somewhat scrambled by our relationship to screens, and videos and depth.”

When asked about how she considers this body of work in light of the events of the last year, Harris laughed, “funnily enough, I started this body of work in October last year, and I think the name [A Stopped World] came to me in around November, so yeah I think I made it happen. I’m sorry guys.”

Words: Ellen Ormesher