The Importance of Slowing Down

The relentless pressure and pace of our capitalist reality means that most of us have become accustomed to moving through life at a hundred miles per hour. Social acceleration is a structural necessity to what has been termed ‘turbo-capitalism’, where economies are rooted in constant market innovation and competition. Problematically, our current cultural orientation equates speed with progress and success.

Jia Aili, Sontain, 2019

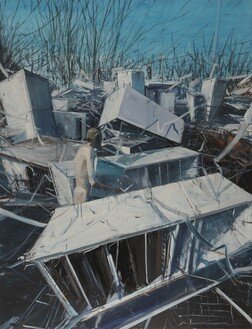

Jia Aili, The Wasteland, 2007

In light of this, experiencing lockdown was surreal. With very little warning, everything stopped. Life became slow, aimless, uncertain, and most of all different. If you were not a key worker, you were no longer moving fast. You simply were not allowed to. This sudden and government-enforced general slowing-down-of-things was in many ways damaging, jarring and unwelcome, but it also prompted reflection on the pace of life that we mindlessly adhere to. It turns out, there is a lot to be said for slowing down.

Over the past few decades, attention has been directed towards slowness in relation to wellbeing. Carl Honoré’s In Praise of Slow (2004) granted cultural establishment to what is now known as the Slow movement, ‘a cultural revolution against the notion that faster is always better’. Sub-movements propose sustainable alternatives to notoriously speedy, mass-production based industries - for example, slow fashion and slow food oppose the rapid consumerism of fast food and fast fashion. Despite specific applications, the Slow movement is not centrally organised: its philosophy is individually propounded and applicable to any aspect of life. It does not reject the modernised present, or idealise the pre-industrial past. In simple terms, it is about being reflective in finding the right pace, prioritising quality over quantity, and ‘challenging the cult of speed’.

Relentless societal acceleration has been criticised in art as well as literature. Notable here is the work of Beijing based painter Jia Aili, who paints dark and whirling dystopian images on enormous canvases. Although they engage specifically with China’s rapid and dramatic societal transformations, his paintings invoke a hurtling speed that feels universally modern. The world Aili depicts is littered with the detritus of industry: in The Wasteland (2007), a lonely figure moves through what looks like a landfill for battered and abandoned filing cabinets. Some images are more strikingly harrowing, for example The Young (2012). Death clings on to an infant figure who walks through the centre of a dark and jagged tornado. Sharp fragments, fires and collisions populate his canvases, and paintings like Sontaine (2019) invite us to consider the ensuing chaos and self-destruction of rapid technological and industrial innovation. Aili’s work reads like a warning: what will the future look and feel like if it is determined by a ‘cult of speed’?

Jia Aili, The Young, 2012

This ‘cult of speed’ is pervasive, even in a sector like the arts, where (perhaps more so than anywhere else) quality takes precedence over quantity. Despite plenty of evidence that experiencing art has a positive impact on our wellbeing, on average, our encounters with visual art are fleeting. Research shows that gallery visitors spend an average of 27 seconds looking at a piece of art. This statistic shows a gaping disconnect between the general consumption of art and the creative endeavour of artists – who want their viewers to slow down and really take in the work. Fast looking feels sadly, but unsurprisingly, symptomatic of our societal drive for rapid production and consumption.

Rebecca Chamberlain, psychology lecturer at Goldsmiths University, has set out to address this in her research. In 2019 she led a sold-out ‘Slow Looking Tour’ of Tate Modern’s 2019 Pierre Bonnard exhibition, encouraging participants to embrace the rewards that slowness has to offer. Chamberlain’s theories about slow looking are underpinned by the success of art therapy as a treatment for anxiety; she asks, might the mental benefits of making art also be applicable to the experiences of looking at it? It seems a great shame that gallery-goers rarely pay deep and sustained attention to artworks, seldom engaging with them slowly and thoughtfully.

Slow looking combats this. It necessitates that we stop, let emotions rise, and really sit with them. Combining slowness with art’s capacity for absorption, as a practice it encourages introspection and is mindful to the core. Comprehending lockdown mindfully was incredibly hard if not impossible: it brought with it innumerable new difficulties, and slowing down feels unnatural to us at the best of times.

Perhaps being slow is perhaps more about reflection than stasis. A long, slow look at the work of Aili is perhaps enough to trigger an acknowledgement of the destruction and alienation that heedless speed might bring. Occasional slowness could benefit us all, and slow looking might just be the perfect escape from our societal speed cult.

Words: Alice Keeling